Muslim apologists love to tout polygamy as some kind of progressive reform in Islam. They’ll tell you that before Islam, Arab men could marry as many women as they pleased, and Islam swooped in to cap it at four wives—sometimes even claiming it pushes for just one. It’s a tidy little story, repeated so often it’s taken as gospel. But here’s the problem: it’s not true according to Tafsir Al-Razi, a heavyweight Quranic commentary by Imam Fakhr Uddin Razi. In his analysis of Surah Nisa, Ayat 3, Razi rips apart the idea that the Quran limits men to four wives—or one. Let’s dive into this mess and see what’s really going on.

The Apologetic claim

The standard line goes like this: “Polygamy was rampant in pre-Islamic Arabia, and Islam restricted it to four wives, or better yet, encouraged monogamy.” Plenty of Islamic scholars back this up, pointing to Surah Nisa, Ayat 3—“Marry those that please you of women, two, three, or four”—and saying that’s the hard limit. Some even stretch it to argue the verse prefers one wife, citing the bit about fairness. It’s a comforting narrative for those trying to sell Islam as restrained or equitable. But Tafsir Al-Razi throws a wrench into it, arguing the Quran sets no such limit. And Razi’s not some obscure nobody—his work is a cornerstone of classical Islamic scholarship.

Tafsir Al-Razi: No Cap on Wives

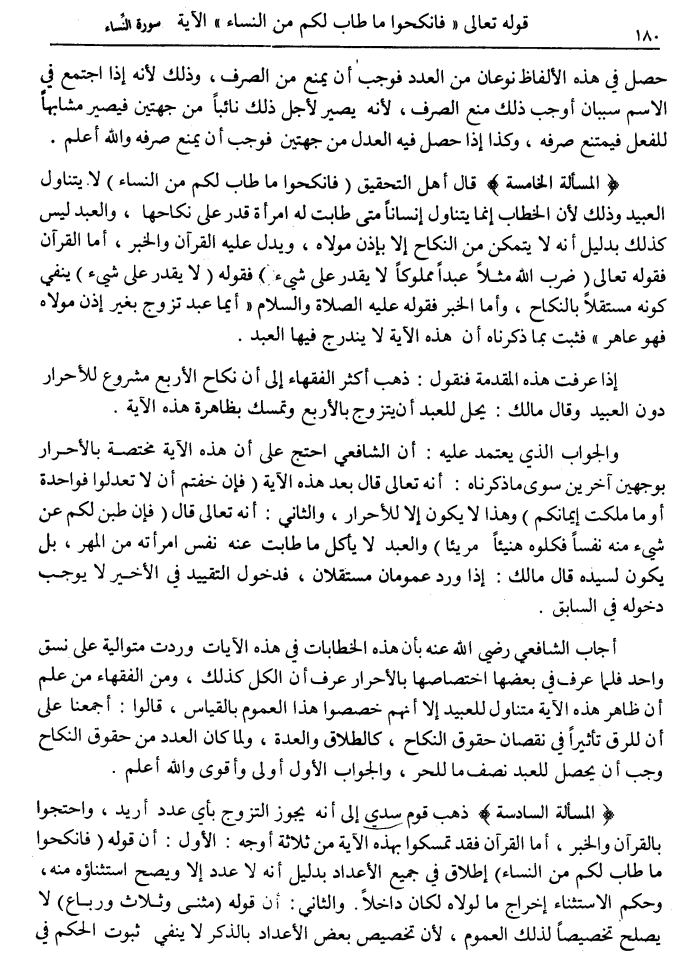

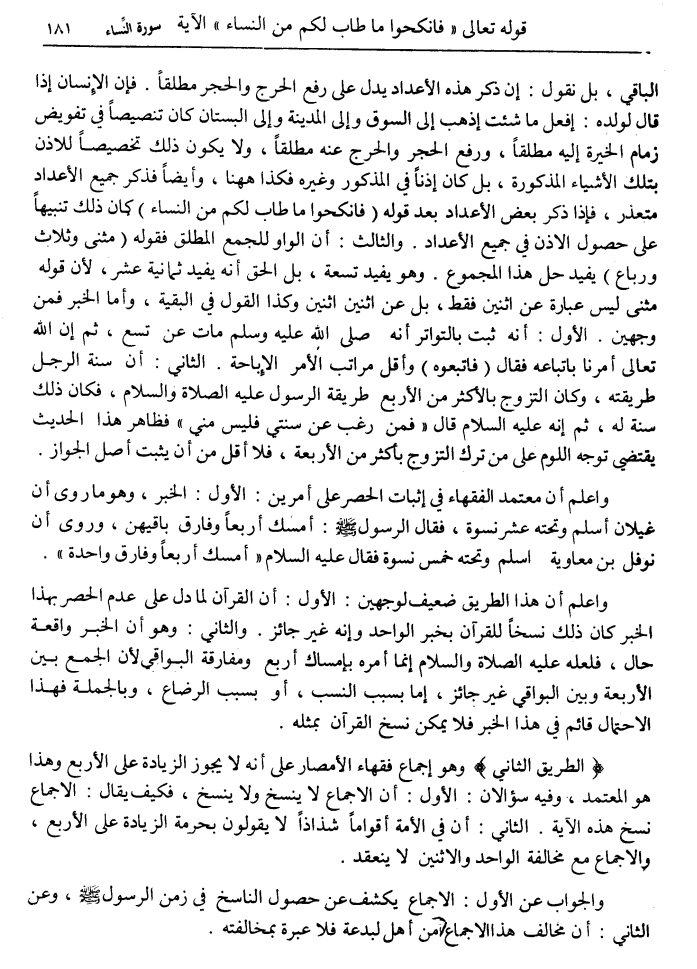

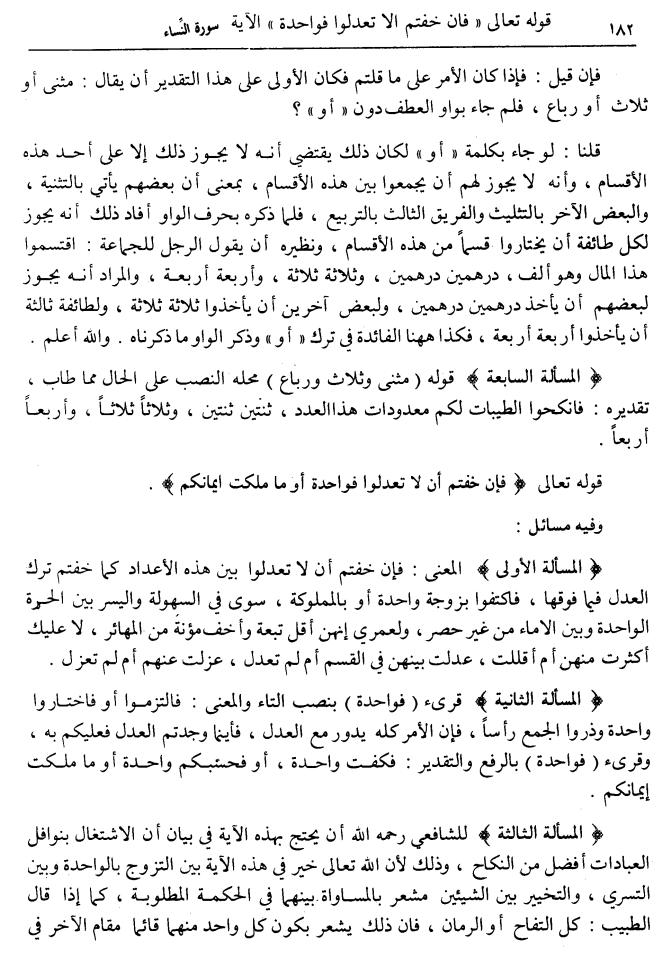

In Tafsir Al-Razi, Volume 9, Surah Nisa – Ayat 3, Issue No. 6 (المسألة السادسة), pages 180-182, Razi lays out a brutal case that the Quran doesn’t restrict polygamy to four—or any number. Here’s the original Arabic text, followed by my own English translation:

Arabic Text:

المسألة السادسة ذهب قوم سدي إلى أنه يجوز التزوج بأي عدد أريد، واحتجوا بالقرآن والخبر، أما القرآن فقد تمسكوا بهذه الآية من ثلاثة أوجه: الأول: أن قوله (فانكحوا ما طاب لكم من النساء) إطلاق في جميع الأعداد بدليل أنه لا عدد إلا ويصح استثناؤه منه، وحكم الاستثناء إخراج ما لولاه لكان داخلاً. والثاني: أن قوله (مثنى وثلاث ورباع) لا يصلح تخصيصاً لذلك العموم، لأن تخصيص بعض الأعداد بالذكر لا ينفي ثبوت الحكم في الباقي، بل نقول: إن ذكر هذه الأعداد يدل على رفع الحرج والحجر مطلقاً. فإن الإنسان إذا قال لولده: إفعل ما شئت إذهب إلى السوق وإلى المدينة وإلى البستان كان تنصيصاً في تفويض زمام الخيرة إليه مطلقاً، ورفع الحجر والحجر عنه مطلقاً، ولا يكون ذلك تخصيصاً للإذن بتلك الأشياء المذكورة، بل كان إذناً في المذكور وغيره فكذا ههنا، وأيضاً فذكر جميع الأعداد متعذر، فإذا ذكر بعض الأعداد بعد قوله (فانكحوا ما طاب لكم من النساء) كان ذلك تنبيهاً على حصول الإذن في جميع الأعداد. والثالث: أن الواو للجمع المطلق فقوله (مثنى وثلاث ورباع) يفيد حل هذا المجموع. وهو يفيد تسعة، بل الحق أنه يفيد ثمانية عشر، لأن قوله مثنى ليس عبارة عن اثنين فقط، بل عن اثنين اثنين وكذا القول في البقية، وأما الخبر فمن وجهين. الأول: أنه ثبت بالتواتر أنه صلى الله عليه وسلم مات عن تسع، ثم إن الله تعالى أمرنا باتباعه فقال (فاتبعوه) وأقل مراتب الأمر الإباحة. الثاني: أن سنة الرجل طريقته، وكان التزوج بالأكثر من الأربع طريقة الرسول عليه الصلاة والسلام، فكان ذلك سنة له، ثم إنه عليه السلام قال (فمن رغب عن سنتي فليس مني) فظاهر هذا الحديث يقتضي توجه اللوم على من ترك التزوج بأكثر من الأربعة، فلا أقل من أن يثبت أصل الجواز.

English Translation:

The sixth issue: A group, including Suddi, argued that it’s permissible to marry any number one desires, and they backed this with the Quran and Hadith. As for the Quran, they relied on this verse in three ways:First, the statement “Marry those that please you of women” is a general permission for all numbers, since there’s no number that can’t be excepted from it, and the rule of exception is to exclude what would otherwise be included.

Second, the phrase “two, three, or four” doesn’t restrict that general permission, because mentioning some numbers doesn’t negate the ruling for others. Rather, we say: mentioning these numbers shows the complete removal of restriction or prohibition. For instance, if a man tells his son, “Do what you want: go to the market, the city, or the garden,” it’s a full delegation of choice and lifts all limits, not a restriction to those specific places. It’s permission for what’s mentioned and beyond—so it is here. Also, listing all numbers is impossible, so mentioning some after “Marry those that please you of women” signals permission for all numbers.

Third, the “and” in “two and three and four” implies an unrestricted total. This could mean nine, or even eighteen, since “two” doesn’t just mean two but pairs of two, and so on.

As for the Hadith: First, it’s proven by continuous transmission that the Prophet (peace be upon him) died with nine wives, and Allah ordered us to follow him, saying “So follow him,” and the least degree of a command is permissibility. Second, a man’s Sunnah is his way, and marrying more than four was the Prophet’s way, making it his Sunnah. He said, “Whoever turns away from my Sunnah is not of me,” suggesting blame for those who avoid marrying more than four, so at minimum, it establishes permissibility.

Razi’s take is blunt: the Quran doesn’t cap wives at four. The verse “Marry those that please you of women” is wide open, and “two, three, or four” are examples, not a ceiling. He even points to Muhammad’s nine wives at death as proof—hardly the move of a guy bound by a four-wife rule.

Razi’s Arguments, Step by Step

Let’s break this down:

- Open-Ended Permission: The verse kicks off with “Marry those that please you of women.” No limits, no numbers—just marry who you want. Razi says this is a blank check, and any number can fit unless explicitly ruled out. Four isn’t a cap; it’s just part of the picture.

- “Two, Three, or Four” Isn’t Restrictive: Razi argues that listing specific numbers doesn’t mean you stop there. It’s like saying, “Eat what you want: apples, oranges, or bananas.” You’re not banned from mangoes. Mentioning two, three, and four just shows polygamy’s fine—it doesn’t forbid five or ten. In fact, Razi says it lifts all restrictions.

- The Prophet’s Nine Wives: Muhammad had nine wives when he died. If four was the limit, why didn’t he stick to it? Razi says this proves the rule: marrying more than four is allowed, even encouraged, since following the Prophet’s way is a big deal in Islam. That Hadith—“Whoever turns away from my Sunnah is not of me”—hits hard. Limiting yourself to four could mean rejecting his example.

The Pushback

Scholars who cap it at four lean on two things:

- Hadiths: Stories like Ghumaylan, who had ten wives and was told by Muhammad to keep four and ditch the rest, or Nawfal bin Muawiya, who had five and was told to drop one. These are used to argue four’s the max.

- Consensus (Ijma): Most jurists say you can’t go past four, claiming scholarly agreement locks it in.

Counterarguments:

- Hadiths Don’t Cut It: They’re specific incidents, not universal rules, and maybe those extra wives were invalid for other reasons—like family ties or foster relations. Plus, you can’t override the Quran’s broad permission with shaky, single-narrator Hadiths. That’s a non-starter in Islamic law.

- Consensus Is Bogus: There’s no true consensus. Some scholars, even if a minority, allowed more than four. If even one or two dissent, the “agreement” falls apart. He calls it a flimsy excuse to rewrite the Quran.

What’s the Real Deal?

If Razi’s right—and he’s got a damn good case—the apologetic claim that Islam restricted polygamy to four (or one) is a load of crap. The Quran’s vague wording leaves the door wide open, and Muhammad’s own life slams it shut on the four-wife limit. Apologists can twist themselves into knots, but Tafsir Al-Razi exposes the truth: there’s no cap. Polygamy’s as unrestricted as it was before Islam, just dressed up in holier language.

Screenshot of eBook Pages Referenced: